“What time is it?” you ask, as we stroll through the horological garden.

“Well,” I say, casting a casual eye over the flowerbeds, “The ice-plant is closed, but the madwort is still open, so it is somewhere between three and four.”

At this point, you abandon our excursion in search of someone with a stronger tether to reality or, at least, a watch. I’m left alone, glorying in my chronobiological expertise, unbudgingly smug.

Sigh. A girl can dream.

The Horologium Florae – the flower clock – is botany’s most whimsical contrivance. As certain species of flower open and close at certain hours of the day, a cleverly assembled flowerbed could allow an onlooker to tell the time. Or so the theory goes.

I first came across the idea of a floral clock in Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels. It’s one of those notions so delightful it lodges immediately in the subconscious.

Pratchett’s most detailed description of a floral clock concerns the monk Lu-Tze’s Garden. He walks through the monastery with his apprentice, Lobsang, in Thief of Time:

‘I wonder what time it is,’ said Lu-Tze, who was walking ahead.

Everything is a test. Lobsang glanced around at the flowerbed.

‘A quarter past nine,’ he said.

‘Oh? And how do you know that?’

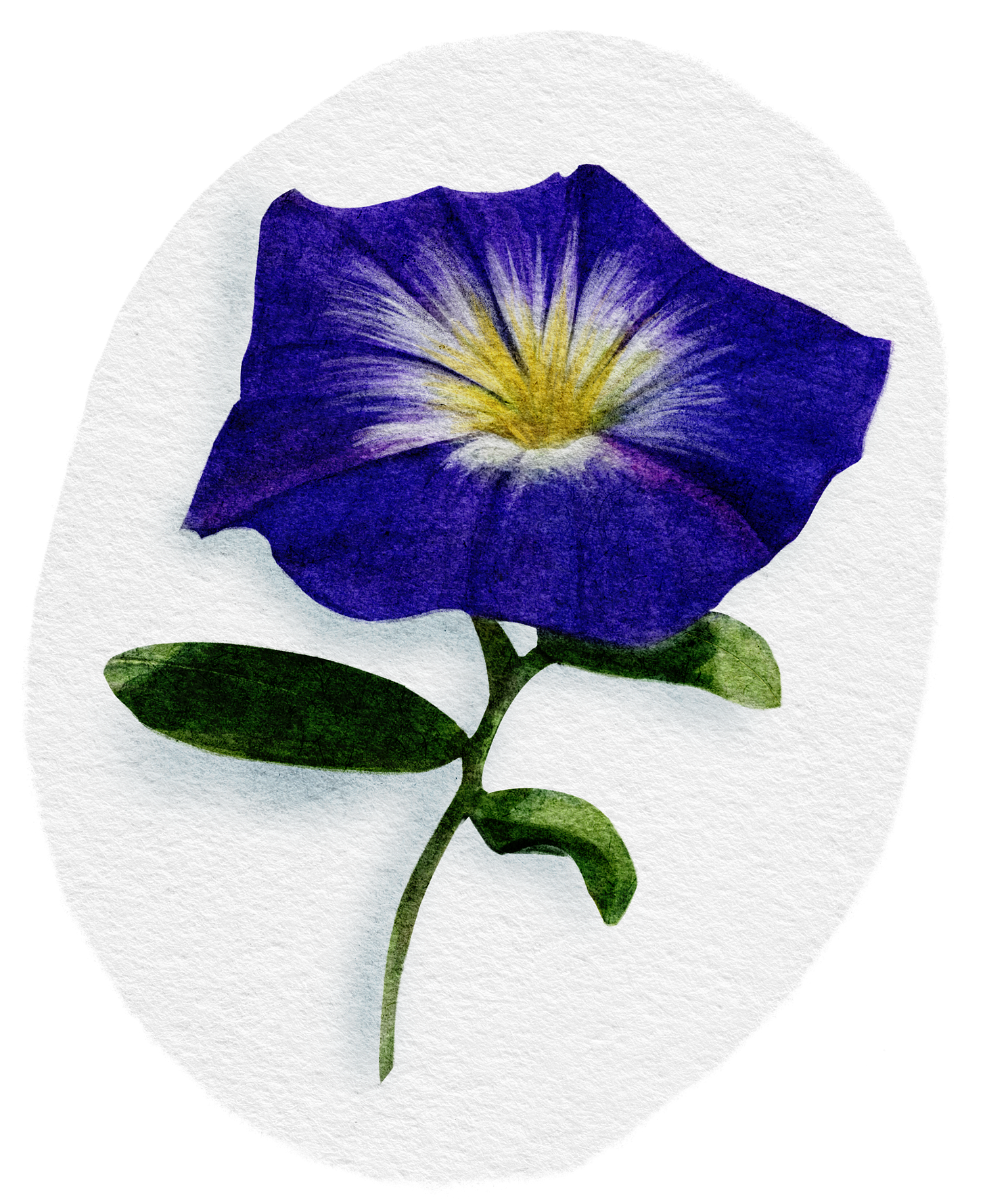

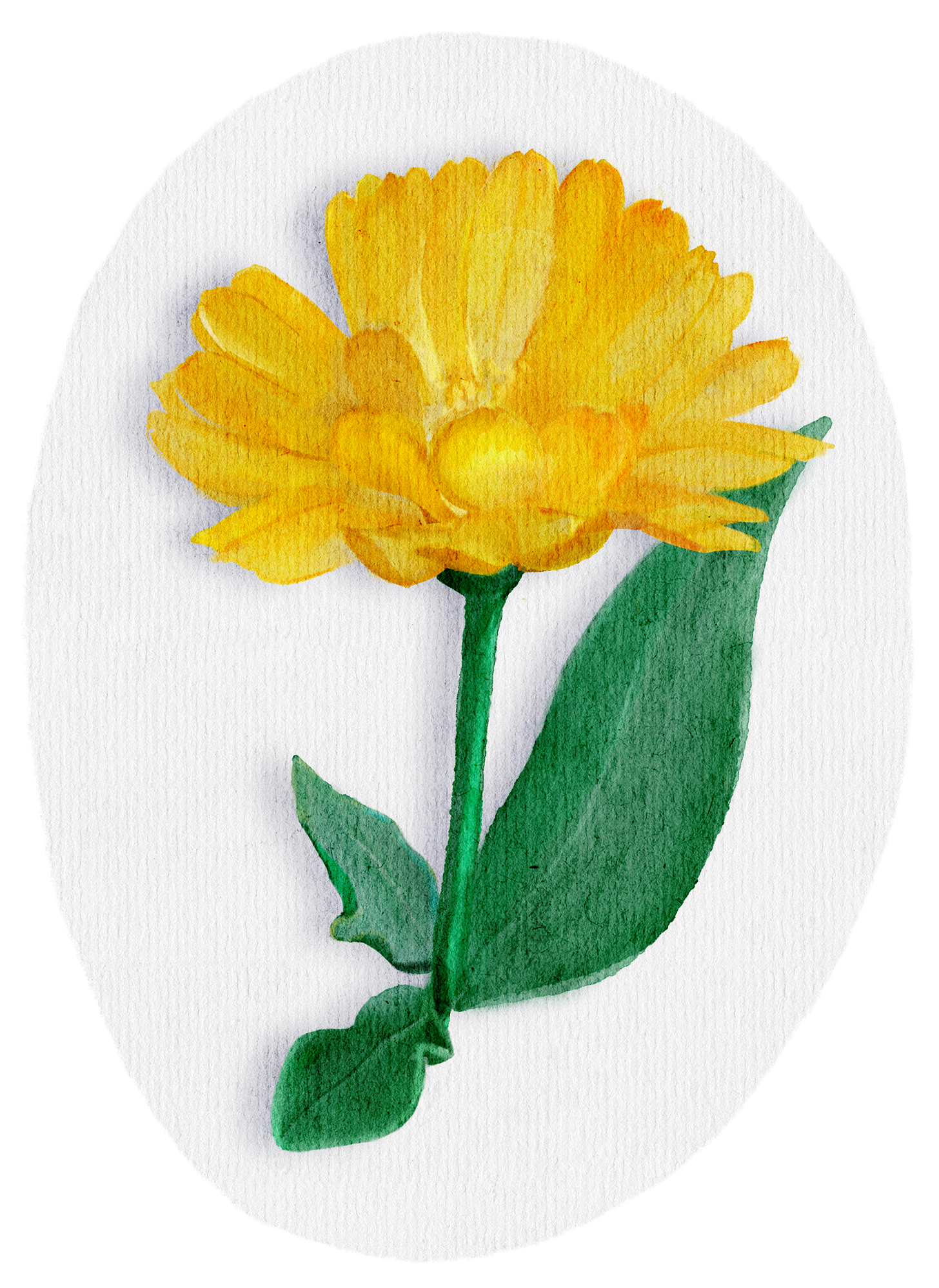

‘The field marigold is open, the red sandwort is opening, the purple bindweed is closed, and the yellow goat’s beard is closing,’ said Lobsang.

‘You worked out the floral clock all by yourself?’

. . .

‘It’s not very accurate in the small hours. There aren’t too many night-blooming plants that grow well up here. They open for the moths, you know-’

‘It’s how time wants to be measured,’ said Lobsang.

Isn’t that lovely? You can see why the idea filed itself in my internal whimsy cabinet, sub-category: ‘fiction’.

But I should have done a little more research, as it seems Pratchett found this curiosity on Roundworld1. A while ago, I was listening to an episode of Planthropology. Ecologist Natalie Sabin brought up Carl Linnaeus, the father of taxonomy, and his curious conception of the Horologium Florae.

I startled. This fantastical concept germinated in our world.

Armed with new search terms, I bypassed the many “floral clocks” that are merely flowers planted in the shape of a clock (pah!), and found NYT’s excellent article on the topic: Five Minutes to Moonflower. That sent me down a rabbit-hole.

Cosmos from chaos

Let’s start with the man who seems to have come up with the idea: Carl Linnaeus.

Linnaeus was born in 1707 in Råshult, a village in southern Sweden. The son of a poor curate, he had an early interest in botany and, after a rocky academic start, became an excellent student.

As a young man he skirted destitution, studying medicine while barely able to afford lecture fees. But he received mentorship from some fine scientists – and, eventually, financial help from wealthy people he impressed – and so began producing catalogues of species while still in his 20s.

The first edition of Systema Naturae was published in 1735. Just a few pages long, it laid out a wonderfully simple hierarchical system of taxonomy.

Here was Linnaeus’s greatest talent, and his great legacy: classification. Botany and zoology suffered from overly long naming conventions, multiple names for the same species, and wildly inconsistent taxonomy.

Linnaeus used his new system to overhaul the confused categorisation, stripping names to their bare bones. He identified plants with multiple or inconsistent names and, in short, sorted out the mess.

As Bill Bryson wrote in A Short History of Nearly Everything:

To make these excisions useful and agreeable to all required much more than simply being decisive. It required an instinct - a genius, in fact - for spotting the salient qualities of a species.

Linnaeus soared to prominence, quickly establishing a solid scientific reputation that allowed him to continue research, writing, and publication without further financial strain.

Through the decades, Linnaeus would write and publish many more volumes of carefully categorised lists of species. The Linnean system of classification became the foundation of modern taxonomy. As one biography, in a late 1800s edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, puts it:

He found biology a chaos; he left it a cosmos.

Linnaeus maintained a penchant for plant life. In various books he laid out philosophies and frameworks for his “reformation of botany.” But he seemed determined to catalogue the entire natural world. The 12th edition of Systema Naturae, the last published during his lifetime, comprised 2,300 pages over three volumes, published between 1766 and 1772.

He also managed, I should add, to lay the groundwork for scientific racism of later centuries by putting mankind into four predictably racist categories. This is a good piece on the subject, by the Linnean Society.

Linnaeus was incredibly vain – although not without reason. His legacy is gargantuan, and the importance of his work was obvious well before his death in 1778. But, as Bryson said,

Rarely has a man been more comfortable with his own greatness.

He apparently suggested his grave be inscribed Princeps Botanicorum, ‘Prince of Botanists.’

Even the otherwise doting entry in my old Britannica notes that:

. . he was constantly receiving presents and praise from crowds of correspondence in every civilized country and in every station of life; hence it is not surprising that this universal homage should have bred the vanity which disfigures the latter part of his diary.

Bear with me. We have a tangent-in-a-tangent: the secret sex life of plants

Part of Linnaeus’s explosive popularity was, it seems, his habit of scattering sexual terms and extended saucy metaphors throughout his work.

This was perhaps most notable in his Sexual System of botanical classification.

He classified plants by their sexual characteristics – their stamens and pistils or, as he insisted on putting it, their husbands and wives. This system has, unsurprisingly, been superseded. He also gave many species – animal as well as vegetable – designations such as Clitoria, Fornicata, and Vulva; and wrote purple prose about the sex lives of flowers.

The flowers’ leaves serve as a bridal bed, which the Creator has so gloriously arranged, adorned with such noble bed curtains, and perfumed with so many soft scents that the bridegroom with his bride might there celebrate their nuptials with so much the greater solemnity. When the bed has thus been made ready, then is the time for the bridegroom to embrace his beloved bride and surrender himself to her.

And it didn’t stop with him!

Erasmus Darwin, Charles Darwin’s grandfather, delighted and scandalised his contemporaries with his anonymously published poem The Loves of the Plants, which was meant as an illustration of Linnaeus’s sexual system. Here’s a short extract:

With secret sighs the Virgin Lily droops,

And jealous Cowslips hang their tawny cups.

How the young Rose in beauty’s damask pride

Drinks the warm blushes of his bashful bride;

With honey’d lips enamour’d Woodbines meet,

20 Clasp with fond arms, and mix their kisses sweet.–

It was later published in its full form, and under Erasmus’s name (once he’d established that people weren’t planning on exiling the author), as The Botanic Garden. It is an interdisciplinary piece of scientific erotic poetry. What a niche.

The Flower Clock

Anyway. Gosh. Where were we?

Linnaeus first came up with the idea of a Horologium Florae in 1748. He published the concept in Philosophia Botanica, in 1751. In this book, he described three types of flower:

Meteorici – flowers which change their opening and closing times according to the weather

Tropici – flowers which change their opening and closing times according to the length of the days

Aequinoctales – flowers that open and close at fixed times each day

Only the third category would be of any good to his Horologium Florae; and so from the third he drew his clock.

The Philosophia Botanica lists plants with predictable opening and closing times, including white waterlily, marigold, sand spurrey (also known as red sandwort), bindweed, and goat’s beard.2 You can see the translated list on Wikipedia – here’s a small sample:

Tragopogon hybridus

Goat’s-Beard

Opens: 03:00Convolvulus tricolor

Dwarf/tricolour morning glory

Opens: 05:00Petrorhagia prolifera

Proliferous/childing-pink

Opens: 08:00

Closes: 13:00Mesembryanthemum crystallinum

Ice-plant

Opens: 09:00-10:00

Closes: 15:00Alyssum alyssoides

Pale madwort/yellow alyssum

Closes:16:00Hemerocallis lilioasphodelus

Day-lily

Closes: 19:00-20:00

Linnaeus’s autobiographical notes were predictably self-aggrandising:

Horologium Florae, to see by the opening and closing of flowers what the time is, from morning to evening, was also invented by L. for the benefit of the world.

He was sweetly optimistic about his idea, despite its impracticality. If one only gathered the correct plants, he theorised, one could tell the time accurately – as accurately as a watch, he said, although surely he was exaggerating – by the flowers alone.

And it was not a passing fancy. According to the University of Uppsala:

He spent much of his time within the confines of the botanic garden, both winter and summer. There he could monitor at close quarters, day and night, the changes occurring in the plants growing in the beds and the orangery.

He also wrote at length about plants changing with the seasons in Calendinium floarae (the flower almanack) and describes how different plants prepare for night-time in Somnus plantarum (the sleep of plants).

Linnaeus’s son, also Carl, was earmarked from childhood to continue his father’s observations. Young Carl started a thesis titled Horologium plantarum as a teenager, but it seems the project was never completed.

Indeed, all the sources I found said it’s unlikely that either Linnaeus planted a flower clock.

But that didn’t stop it rooting in the popular imagination.

Popular horticulture

In the late 1700s, Charlotte Smith3 wrote a poem called The Horologie of the Fields:

In every copse, and shelter’d dell,

Unveil’d to the observant eye,

Are faithful monitors, who tell

How pass the hours and seasons by.

Victorians were, predictably, very into the idea of a floral clock; as were, and are, many others.

The French composer Jean Françaix was inspired in the 1950s to write L'Horloge de Flore4, a work whose seven movements go from 5 heures (Cupidon Bleu), (Cupid’s Dart or Blue Catananche), to 21 heures (Silène noctiflore), (Night-Flowering Catchfly).

In the digital realm, the idea captured the imagination of developers at optional.is, who created a beautiful Apple Watch “Floræ” complication in 2017. The 24-flower clock is, the creators say, “a silly little folly that [the Victorians] would be proud of.”

Out of reach

Plants in the physical world aren’t as cooperative as programmed petals. Flowers don’t open and close as predictably as a budding florologist might hope.

As Linnaeus noted, a flower’s circadian rhythm can be affected by factors such as season, latitude and temperature. What he didn’t realise is that flowers don’t fit cleanly into his initial three categories. In fact, botanists are still discovering elements of complexity– for instance, it seems that some flowers may ‘track’ how many insects have visited and close up early after a busy day.

The partial flower clocks that have been built suffer from visual similarities between species. Yellow, dandelion-like blooms are hugely over-represented in the original, Northern European version of the clock.5

There’s also the problem of night flowers.

Lu-Tze’s clock, though more successful than its Roundworld counterparts, met a stumbling block that parallels one of many obstacles in our dimension: a lack of night-blooming plants.

Most flowers – especially in the latitudes in which Linnaeus worked – open in the morning, to greet the flying insects and warmer air. By afternoon, Linnaeus’s clock relies only on blooms closing. It stops entirely at 8pm.

If we allow our search to span the earth, we do find more variety in wildflower hue and even a few flowers that open, as Lu-Tze says, for the moths. The moonflower, found in the Americas, is a beautiful example: it unfurls its large, white bloom rapidly – within a minute! you can watch it! – around 9pm. It doesn’t close until its petals feel the morning dew.

Still, the conceptual clock is far from complete; even if you mix and match plants from incompatible latitudes, and add a pond for water lilies, and pretend we understand the intricacies of chronobiology. For now, it is still a dream.

A perennial dream

The dream is recurring. Botanists, gardeners, and artists in various countries and in various centuries have tried their hand at building a – generally theoretical – local version of the Horologium Florae.

In 1898, for example, B. B. Smyth wrote an article titled Floral Horologe for Kansas, which lists the opening and closing times of “a goodly number of native flowers and a few naturalized flowers in the state of Kansas”. Smyth lists a huge number of plants, including many evening blooms. It’s also beautifully illustrated – I recommend having a look.

The Linnaean Society has received regular enquiries about their namesake’s clock, and how to make one, over the many years of its operation. The University of Uppsala, where Linnaeus studied, maintains The Linnaeus Garden, which contains only plants that were grown by Linnaeus himself. The gardeners are, from what I gather, still mulling over the practicalities of a floral clock.

Even Linnaeus might not have been the first to come up with the idea– a poem by Andrew Marvell written in 1678 could well describe a floral clock:

How well the skilful gardener drew

Of flow’rs and herbs this dial new;

Where from above the milder sun

Does through a fragrant zodiac run;

And, as it works, th’ industrious bee

Computes its time as well as we.

How could such sweet and wholesome hoursBe reckoned but with herbs and flow’rs!

For the thought of a Horologium Florae is unavoidably delightful. It’s one of those ideas that keeps trying to leak back – through poems, paintings, and the whims of gardeners. Even if it isn’t quite built for our corner of the multiverse.

Although I suppose, given the peculiarities of L-Space, it might have been the other way around.

All of which you will recognise from the Thief of Time extract we read earlier.

Smith was a very interesting botanist and poet in her own right – I’ll write a separate article on her.

You can read an analysis of L’Horloge de Flore here, and see it performed here.

I would argue that embracing this might train us to appreciate the nuances of a dandelion. And not just because I can’t be bothered to get them out of the lawn.