One of the quiet delights of literary history is the occasional discovery that your heroes knew – better still, supported and inspired – one another.

In England, at least, this is often a side effect of the country’s cloistered bunch of elite universities. Still, just for now, let’s not hold that against the memory of brilliant men, smoking pipes, enjoying a drink and putting their imaginary worlds to rights.

Among them are two giants: J. R. R. Tolkien1 and C. S. Lewis.

I started my reading expecting to write about a professional relationship and a petty falling-out. The actual story is rather sweeter. Tolkien and Lewis had a meaningful friendship, and each harboured deep respect for the talent of the other. Each, also, had a huge influence on the other’s career.

Reading Tolkien’s letters gives us a glimpse of the hurt he felt as their friendship faltered.

But let’s not start at the end. First, we set the scene.

Young lives

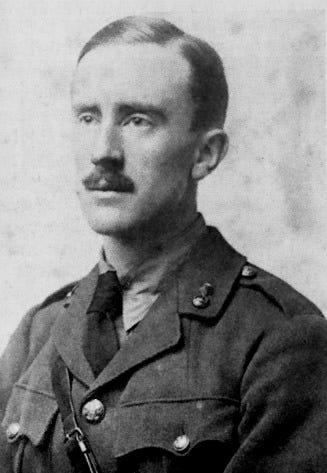

J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was born on 3 January 1892, in South Africa. His father died when Tolkien was three, turning a family visit to England into a permanent move.

Tolkien was exceptionally fond of his mother, Mabel, who taught him at home. She encouraged him to read and fostered his love of botany. In 1900, Mabel Tolkien (née Suffield) converted to Catholicism – a decision which cut her off from all family support.

Tolkien admired her bravery and, when she died of diabetes aged just 34, he thought of her as a martyr.

. . . she was a gifted lady of great beauty and wit, greatly stricken by God with grief and suffering, who died in youth (at 34) of a disease hastened by persecution of her faith. (The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter 44)

Before her death, Mabel made a decision that would grant Tolkien the protection and tutorage he needed – she appointed Father Francis Xavier Morgan as the guardian of her two sons. Although it meant the boys had to live a strict, religious life at Birmingham Oratory, the guardianship was the difference between poverty and obscurity and a safe, educated remainder of their youth. Tolkien won and retained a scholarship to a first-rate day school: King Edward’s.

While at the school, he and three friends – Rob Gilson, Geoffrey Smith, and Christopher Wiseman – formed a semi-secret society called the Tea Club and Barrovian Society. This referred to their illicit tea-drinking in the school library and in the nearby Barrow’s Stores. The group remained in close contact after they left the school, and it was following a 1914 reconvening that Tolkien started devoting more time and energy to poetry.

Tolkien secured himself a place at Exeter College, Oxford. He graduated from the university 1915, with a first-class degree in English Language and Literature.

In 1916, he married his childhood sweetheart – well, sort of. The pair had met at the boarding house Tolkien moved to when he was 16 and Edith Bratt, the object of his affections, was 19. According to Humphrey Carpenter’s2 J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography:

Edith and Ronald took to frequenting Birmingham teashops, especially one which had a balcony overlooking the pavement. There they would sit and throw sugarlumps into the hats of passers-by, moving to the next table when the sugar bowl was empty. … With two people of their personalities and in their position, romance was bound to flourish. Both were orphans in need of affection, and they found that they could give it to each other. During the summer of 1909, they decided that they were in love.

Which is almost unbearably sweet, isn’t it?

Sadly for the twitterpated twosome, Father Morgan – Tolkien’s guardian at the time – thoroughly disapproved of Tolkien’s relationship with an older woman (and a protestant to boot!). He forbade Tolkien from meeting her until his 21st birthday. He obeyed, although he found it very painful. But if Father Morgan had hoped the break would be permanent, he was disappointed. As Tolkien wrote later:

On the night of my 21st birthday I wrote again to your mother – Jan. 3, 1913. On Jan. 8th I went back to her, and became engaged, and informed an astonished family.

The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter 43

They married in 1916.

We have now, of course, entered the years defined by World War I. While Tolkien’s lack of enthusiasm for military endeavour was derided by his relatives, the young man had, in fact, joined the army in 1915 and legitimately delayed his deployment to allow him to finish his degree.

But in June 1916, just a couple of months after his wedding, Tolkien received a telegram summoning him to Folkestone, and onwards to France.

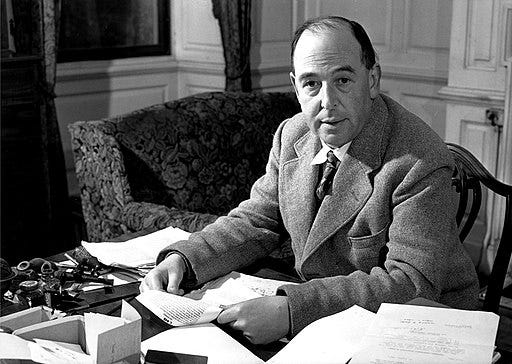

C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis was born on 29 November 1898, in Belfast.

When he was four, his dog, Jacksie, was killed by a car. From then on, Lewis insisted that people call him Jacksie – later shortened to Jack.

He demonstrated a fine imagination from a young age, inventing a world of anthropomorphic animals with his brother.

Lewis’s mother died when he was only nine, and his father was distant and erratic in his care. The boy was sent to boarding school first in England, then back in Ireland, then again to England – this time to Worcestershire.

Here he became an atheist and developed his love of ancient Scandinavian literature. His interest in Norse mythology expanded into the Greek pantheon. He received a scholarship to Oxford University and entered University College in the summer term of 1917.

Unlike Tolkien, Lewis took a proactive approach to military service. He joined the university’s Officers’ Training Course, transferred to Keble College.

He didn’t particularly enjoy Keble but formed close friendships with his roommate Paddy Moore (and Paddy’s mother, Janie), and four other young men on the course: Thomas, Denis, Martin, and Alexander.

Lewis was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant. He arrived at the front line on 29 November 1917 – his 19th birthday.

War

I broke off both biographies here because this is where the youth of each man ended.

It is impossible to overstate the impact World War I had on the psyche of a generation, especially those on the fronts. The hopeless, endless, industrialised killing blindsided soldiers who’d grown up with romanticised tales of derring-do.

Tolkien fought in the Battle of the Somme from July to October 1916. He survived – possibly due to catching trench fever in October and being shipped off to recuperate – but some 300,000 men did not. Among the staggering list of lives lost were Robert Gilson and Geoffrey Smith, his close schoolfriends and fellow members of T.C.B.S.

Lewis saw combat during the German spring offensive. In April 1918, his battalion came under bombardment at Riez du Vinage. A shell killed his sergeant and wounded Lewis – an injury that would eventually see him sent back to England. Lewis’s roommate Paddy had been killed the previous month.

Did the two authors’ experience of war influence their writing?

How could it not?

In French Nocturne (Monchy-Le-Preux), we see the Battle of Arras through Lewis’s eyes:

The jaws of a sacked village, stark and grim;

Out on the ridge have swallowed up the sun,

And in one angry streak his blood has run

To left and right along the horizon dim.

His fiction would harbour echoes of the same sentiment. Lewis was not a pacifist, but he didn’t sanitise warfare in his books (although obviously he softened the nightmarish tone for children’s books). He approached the topic with a tone of hard practicality. War was necessary at times, but certainly not dulce et decorum.

While Tolkien recovered in a Birmingham hospital, he laid some of the foundations of Middle Earth. The story of Gondolin, written in an exercise book, depicted a beautiful civilisation torn asunder by war3.

He maintained that neither WWI nor WWII “had any influence upon either the plot [of The Lord of the Rings] or the manner of its unfolding,” but added, “Perhaps in landscape.”

“They lie in all the pools, pale faces, deep deep under the dark water. I saw them: grim faces and evil, and noble faces and sad. Many faces proud and fair, and weeds in their silver hair. But all foul, all rotting, all dead.”

The Lord of The Rings– Frodo’s description of the Dead Marshes

The Dead Marshes, Tolkien said, owed “something” to the aftermath of the Battle of the Somme, but owed more to William Morris’s House of the Wolfings or The Roots of the Mountains.

And yet, when Merry crawled “like a dazed beast” on the fields of Pelennor, when Sam and Frodo trudge, shell-shocked and resolute towards Mount Doom… surely there we glimpse soldiers on the Western Front.

On top of the human cost, trench warfare devastated the European countryside, ripping into the natural world prized by Tolkien and Lewis. And so we see the War again in the acrid, choking fumes of Mordor – the grim despoiling of Middle Earth.

But we also find Tolkien’s experience of war in his inspiring passages. The class-spanning friendships reflect the relationships that Tolkien formed with batmen and officers alike – all men brought together to find camaraderie in unimaginable horror. The march of the ents perhaps scratched a decades-long itch to see nature reclaim its territory.

Reflecting the global awakening from the delusion of “romantic” warfare, both Tolkien and Lewis wrote heroes who started their journeys ill-equipped and, often, reluctantly. Their protagonists, and heroic supporting characters, summoned bravery in spite of natural timidity – these were not the self-assured heroes of a classical age.

Friendship

We were talking of dragons, Tolkien and I

In a Berkshire bar. The big workman

Who had sat silent and sucked his pipe

All the evening, from his empty mug

With gleaming eye glanced towards us;

‘I seen ’em myself,’ he said fiercely.

• Poem by C. S. Lewis, first published in Rehabilitations, 1939

The lines which Jack gives as examples are not unfortunately entirely accurate examples of Old English metrical devices. The occasion is entirely fictitious. I have never seen a dragon, nor ever seen a man who said that he has. I don’t wish to see either.

• J. R. R. Tolkien, letter to Walter Hooper, 1968 (The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter 300)

Tolkien and Lewis both returned to Oxford after the War, and eventually both would find themselves as part of the university’s English faculty. They met in 1926, an occasion marked in Lewis’s diary. He described Tolkien as a “smooth, pale, fluent little chap.” He went on to note that there was “no harm in him: only needs a smack or so.”

Still, the pair soon latched onto a shared love of language – of verse, storytelling, and mythology. They became close friends, in spite of a Shakespearean separation of houses: Tolkien specialised in Language, while Lewis loved Literature.

Oxford university’s English faculty housed exactly the sort of people you think it did: tweedy, pipe-smoking dons full of mumble and sneer. They turned their ire on Tolkien when he dared find success in trivial matters such as public acclaim; and they spent a lot of time engaged in inter-departmental sniping.

The rivalry between Language and Literature was keenly felt and, to us outsiders, hilarious.

Radio 4’s excellent Tolkien: The Lost Recordings interviewed Professor Tom Shippey, a Tolkien expert who wrote J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. Shippey, a former faculty member himself, said that Tolkien was hated by the entire literary establishment, but that he did not care because he had never been a professor of English Literature (“a poor, shabby bunch in my opinion”) – he was a professor of English Language.

Shippey recalled an English Literature professor shouting down the phone at an interviewer: “Author of the Century? Has the fellow never heard of Proust?”

“Yes, the fellow has heard of Proust, actually,” Shippey said. “Shall we conduct the rest of this interview in French? I bet mine’s better than yours, you monoglot clown.”

Which is possibly the most marvellous insult I’ve ever heard.

Despite this atmosphere, Tolkien and Lewis cultivated a friendship based on professional admiration and personal bonding. They shared traumatic experiences – the loss of parents at a young age, and the terror of war – and they both came out of it with endless curiosity and a fierce desire to preserve the beautiful things in life.

They also shared interests. Tolkien founded an Old Norse reading group that Lewis joined, and both men were budding authors.

L. said to me one day: ‘Tollers, there is too little of what we really like in stories. I am afraid we shall have to try and write some ourselves.’

Lewis wrote to Arthur Greeves – a childhood friend and probably Lewis’ closest – of Tolkien on several occasions. In 1933:

I have told of him before: the one man absolutely fitted, if fate had allowed, to be a third in our friendship in the old days, for he also grew up on W. Morris and George Macdonald.

Lewis, Greeves, and Hooper 1979, Letter 183

The Inklings

From the early 1930s to the late 1940s, Lewis and Tolkien were part of an informal literary discussion group called The Inklings.

According to Tolkien, the original Inklings was founded by an undergraduate named Tangye-Lean, sometime in the mid-1930s. Tangye-Lean asked some dons to become members, and both Lewis and Tolkien obliged. This first iteration of Inklings soon died, but Lewis transferred the name to the “undetermined and unelected circle of friends who gathered about C.S.L., and met in his rooms in Magdelen.”

Lewis and Tolkien’s friendship formed the core of the new group. As Lewis wrote to his brother:

It has also become the custom for Tolkien to drop in on me of a Monday morning for a glass. This is one of the pleasantest spots in the week. Sometimes we talk English school politics: sometimes we criticise one another’s poems: other days we drift into theology or the state of the nation; rarely we fly no higher than bawdy and puns.

Soon, other writers would join the pair. Monday mornings became Thursday nights. Members came from the faculty and the student body alike. Participants could read unpublished manuscripts and receive feedback and take part in lively debate. The group met in several pubs, most notably the Eagle and Child – often called the Bird and Baby, or just The Bird.

Both Tolkien and Lewis were much-admired teachers who captured the imaginations of their students, so to sit with them in the Eagle and Child, breathing in pipe smoke and animated conversation, would have been a fine opportunity for many a man (and it was only men, I’m afraid) of a literary bent. Lewis in particular had a talent for literary criticism. As Tolkien wrote later:

C.S.L. had a passion for hearing things read aloud, a power of memory for things received in that way, and also a facility in extempore criticism, none of which were shared (especially not the last) in anything like the same degree by his friends.

The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter 298, 1967

The Inklings perched in The Bird’s private parlour, and when Tolkien mentions meetings in his letters, the anecdotes often end with some variation on “and I did not start home till midnight.”

These gatherings seemed to be a truly extraordinary example of a creative feedback loop. The energy sparked inspiration in great minds. The meetings were “a feast of reason and flow of soul,” recalled Tolkien. “What I owe them all is incalculable,” wrote Lewis.

Soon-to-be legendary works – The Screwtape Letters, The Lord of the Rings, All Hallows Eve – were read aloud, chapter by chapter, as they were written.

Lies breathed through silver

In a conversation that entered literary legend, Tolkien, Lewis, and fellow Inkling Hugo Dyson argued history, faith, and myth late into the night of 19 September 1931. At one point, Lewis called myths “lies breathed through silver,” which is a fabulous turn of phrase even if you disagree with it. It was also a demonstration of how much Lewis had changed over the years. He had found huge joy in mythology as a child and younger man.

Whereas you or I might agree to disagree, or bring up the argument at the next meeting, Tolkien was moved to write a 148-line poem4, entitled Philomythus [myth lover] to Misomythus [myth hater]. It became known as Mythopoeia.

I will paste here the opening stanza, and one other, and urge you to read the rest at your own leisure – preferably aloud, as I think it’s the best way to enjoy the couplets.

You look at trees and label them just so,

(for trees are ‘trees,’ and growing is ‘to grow’);

you walk the earth and tread with solemn pace

one of the many minor globes of Space:

a star’s a star, some matter in a ball

compelled to courses mathematical

amid the regimented, cold, inane,

where destined atoms are each moment slain.

Later, the poem continues:

He sees no stars who does not see them first

of living silver made that sudden burst

to flame like flowers beneath an ancient song,

whose very echo after-music long

has since pursued. There is no firmament,

only a void, unless a jewelled tent

myth-woven and elf-patterned; and no earth,

unless the mother’s womb whence all have birth.

The heart of Man is not compound of lies,

but draws some wisdom from the only Wise,

and still recalls him. Though now long estranged,

Man is not wholly lost nor wholly changed.

The versified argument was part of a long process of conversion – Tolkien had been guiding Lewis towards Christianity over several years – and it seems to have done its job. Lewis had already returned to theism in 1929 (hesitantly, by his own admission: “In the Trinity Term of 1929 I gave in, and admitted that God was God, and knelt and prayed: perhaps, that night, the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England,”) and he converted to Christianity the week after he received the poem.

Support system

As well as philosophy, the two continued their literary back-and-forth. They supported each other from the start of their careers as authors. Having been given a copy of The Hobbit’s manuscript, Lewis championed it far and wide.

Writing in the Times Literary Supplement_, 2 October 1937, he said:

The truth is that in this book a number of good things, never before united, have come together: a fund of humour, an understanding of children, and a happy fusion of the scholar’s with the poet’s grasp of mythology… The professor has the air of inventing nothing. He has studied trolls and dragons at first hand and describes them with that fidelity that is worth oceans of glib “originality.”

. . .

it must be understood that this is a children’s book only in the sense that the first of many readings can be undertaken in the nursery. Alice is read gravely by children and with laughter by grown ups; The Hobbit, on the other hand, will be funnier to its youngest readers, and only years later, at a tenth or a twentieth reading, will they begin to realise what deft scholarship and profound reflection have gone to make everything in it so ripe, so friendly, and in its own way so true. Prediction is dangerous: but The Hobbit may well prove a classic.

Lewis’s own work would reflect his return to Christianity. He became a renowned theological lecturer and writer, and his works of fiction glistened with religious allegory. He had a hard time finding a publisher for his first novel, Out of a Silent Planet, and Tolkien used his newfound influence to help him along.

In one letter to Stanley Unwin, who would eventually publish Out of a Silent Planet, Tolkien wrote,

“I read the story in the original MS. and was so enthralled that I could do nothing else until I had finished it.”

It was published in 1938 and followed by two sequels. Oxford University celebrated Lewis, although they would never reward him with tenure.

Tolkien received almost the opposite treatment. Although his scholarly work on Beowulf and his translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight had earned him wide academic acclaim, the public success of The Hobbit drew sneers from colleagues. But not from Jack Lewis.

Tolkien described Lewis as his “closest friend from about 1927 to 1940”. Lewis based the main character in Out of the Silent Planet on Tolkien. Tolkien based Treebeard on Lewis.

Despite this mutual admiration, Tolkien and Lewis had very different tastes in literature. As Tolkien wrote:

The most lasting pleasure and reward for both of us has been that we provided one another with stories to hear or read that we really liked – in large parts. Naturally neither of us liked all that we found in the other’s fiction.

Drifting

There doesn’t appear to have been one dramatic event that cooled the friendship between Tolkien and Lewis. Tensions grew as Tolkien expressed his disapproval of Lewis’s rushed turnaround – the seven Narnia books were published in seven years – and of his Christian apologist works like Allegory of Love.

Tolkien’s writing pace was at stark contrast to Lewis’s. He took 17 years to finish The Lord of the Rings, losing himself in rewrites.

“His standard of self-criticism was high and the mere suggestion of publication usually set him upon a revision,” Lewis wrote, “in the course of which so many new ideas occurred to him that where his friends had hoped for the final text of an old work they actually got the first draft of a new one.”

Although he criticised the endless revisions, C. S. Lewis’s feedback didn’t speed things up:

‘When he would say, “You can do better than that. Better, Tolkien, please!” I would try. I’d sit down and write the section over and over.

To tell the truth he never really liked hobbits very much, least of all Merry and Pippin.”

This persistent critical back-and-forth, even if coming from a place of love, must have taken its toll over the years.

One of the couple of surviving letters from Tolkien to Lewis, written in 1948, seems to refer to correspondence following Tolkien’s criticism of a piece Lewis read aloud at a meeting. I think it’s a good example both of how harsh they could be with one another and how deeply it hurt when they fell out.

I regret causing pain, even if and in so far as I had the right; and I am very sorry indeed still for having caused it quite excessively and unnecessarily. My verses and my letter were due to a sudden very acute realization (I shall not quickly forget it) of the pain that may enter into authorship, both in the making and in the ‘publication,’ which is an essential pan of the full process. The vividness of the perception was due, of course, to the fact that you, for whom I have deep affection and sympathy, were the victim and I myself the culprit. But I felt myself tingling under the half-patronizing half-mocking lash, with the small things of my heart made the mere excuse for verbal butchery.

The pair drifted apart. It can’t have been easy – a friendship based on so many shared parts of oneself must hurt as it fades. In 1949, Lewis wrote to Tolkien, “I miss you very much.”

By the 1950s, their relationship was much cooler. As Tolkien said in a draft letter to his son Michael:

We were separated first by the sudden apparition of Charles Williams, and then by his marriage. Of which he never even told me; I learned of it long after the event.

Charles Williams had sidled onto the scene as another member of the Inklings. He was a writer, critic and Anglican theologian who cultivated considerable influence over Lewis. Tolkien never approved of Lewis converting to Anglicanism instead of Catholicism and felt, more generally, that Williams drove a wedge between him and his friend.

Lewis had married Joy Davidman in 1956. Joy was divorced and American, two characteristics of which Tolkien disapproved.

Anchored

But through the rest of their lives, the two authors retained mutual respect and deep fondness. This is the part I hadn’t expected going in – my mental image of bickering academics held no room for the deep foundation of friendship.

In December 1953, Lewis wrote a blurb for the The Fellowship of the Ring, sending it to the publisher (Allen & Unwin) with a letter:

I would willingly do all in my power to secure for Tolkien’s great book the recognition it deserves. Wd. the enclosed be any use? If not, tell me, and I will try again. I can’t tell you how much we think of your House for publishing it.

However, Lewis cautioned Tolkien against using the blurb, saying that association with his name – well-known by now, but controversial in some circles – might do more harm than good. Still, it was used upon Fellowship’s publication in 1954, and it was glowing:

It would be almost safe to say that no book like this has ever been written. If Ariosto rivalled it in invention (in fact he does not) he would still lack its heroic seriousness. No imaginary world has been projected which is at once so multifarious and so true to its own inner laws; none so seemingly objective, so disinfected from the taint of an author’s merely individual psychology; none so relevant to the actual human situation yet so free from allegory. And what fine shading there is in the variations of style to meet the almost endless diversity of scenes and characters–comic, homely, epic, monstrous, or diabolic!

In a letter to Rayner Unwin, Tolkien brought up a surprising (to me) side effect of this blurb – it seems that the “Ariosto remark” was the source of some controversy. Lewis himself was also, as he’d warned, the target of animosity. Touchingly, though, Tolkien added:

. . . in any case I should not have wished other than to be associated with him – since only by his support and friendship did I ever struggle to the end of the labour.

Also in 1954, Lewis left Oxford. Tolkien continued to bat for his friend, negotiating his position as chair in Medieval and Renaissance Literature at Cambridge.

Final parting

Lewis died on 22 November 1963, at the age of 64. Tolkien would outlive the younger man by a decade.

In a letter to his daughter after the funeral, Tolkien wrote:

So far I have felt the normal feelings of a man of my age – like an old tree that is losing all its leaves one by one: this feels like an axe-blow near the roots.

A literary giant, but quite small in reality– he was around 5’9″ and described himself in a letter as “very slightly built, with notably small hands.”

Carpenter also wrote the Mr Majeika series of children’s books. I was very fond of them as a child.

It would later join many other tales in The Silmarillion, published posthumously.

Because of course he was.